“Freedom is the source from which all significations and all values spring. It is the original condition of all justification of existence. The man who seeks to justify his life must want freedom itself absolutely and above everything else.” (Simone de Beauvoir “The Ethics of Ambiguity,” p. 24)

Back in the late 1900s, it was cool to go to college and piss off the parents by majoring in some vague arts and humanities program.

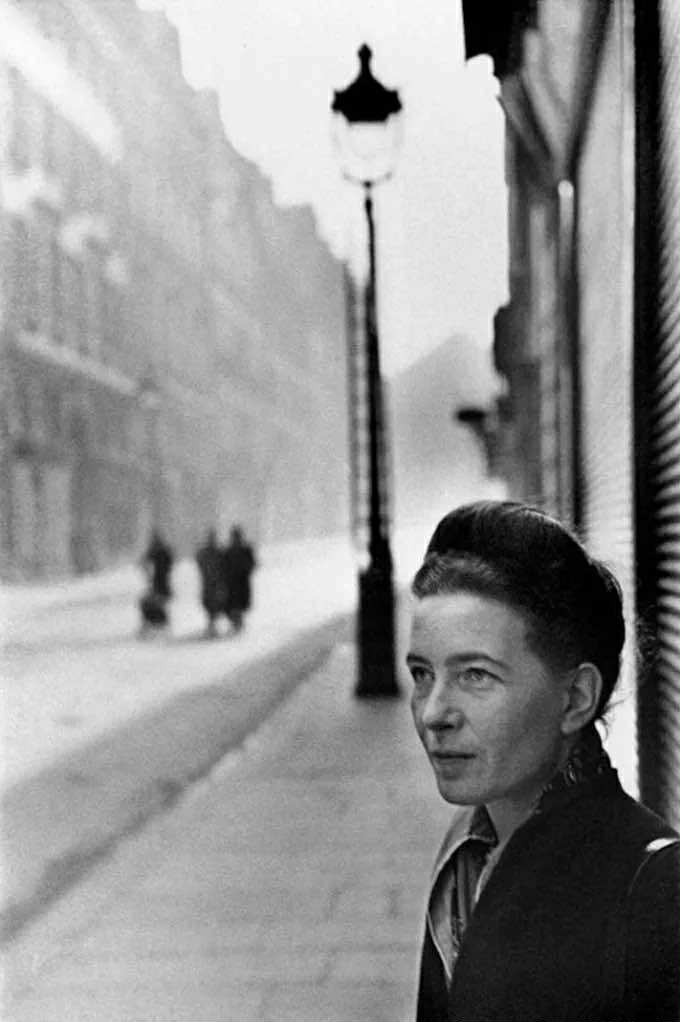

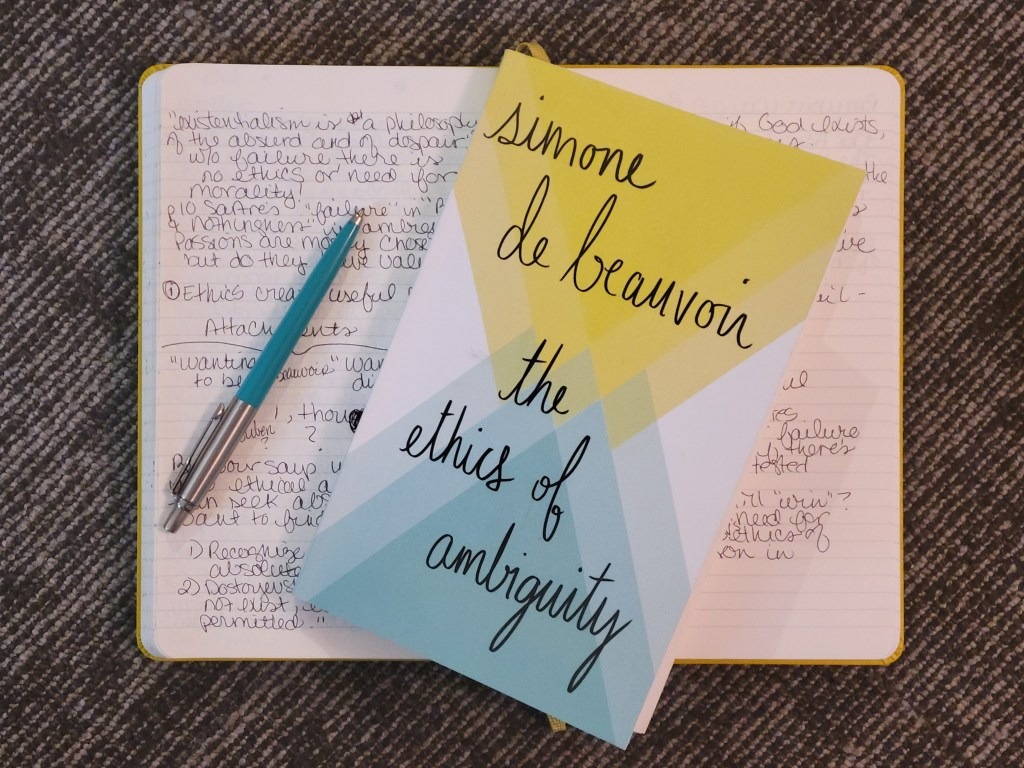

For me, that looked like double majoring in English and Mass Communications with a minor in Women’s Studies, which ultimately introduced me to one of the loves of my life: Simone de Beauvoir (and a lifetime of student loan debt).

Who is Simone de Beauvoir?

Beauvoir, best known for penning “The Second Sex,” was a famous existential French philosopher who spent most of her adult life smoking in cafes and getting into arguments with her long-time beau Jean Paul Sartre and their frenemy and fellow famous thinker Albert Camus.

Cutting to the chase (and ignoring the beards for a hot minute), Beauvoir stood on her own intellectually. She knew how to get her message across. She was a vanguard with a vagina. In fact, I’d say she was an industry thought leader before there were thought leaders!

Revisiting her work more than twenty years after graduating from college has shown me that one of the most influential female minds of the past century is alive and well within the context of our lives as modern writers, thinkers, and communicators.

Beauvoir understood audience personas in a way that resonates so richly today that I almost want to call up Simon Sinek and Brene Brown to discuss.

And it all comes down to SDB’s belief in what she refers to as “Ways of Being” and finding useful passions. The same way brands identify personas, we can identify how we show up as communicators by creating deep, passionate meaning and helping others do the same.

De Beauvoir’s ‘Ways of Being’ 101

Beauvoir’s ethical philosophy is steeped in her belief that the ruling class (the Bourgeoisie) and the working class (the Proletariat) created an existential duality that focused too heavily on their political, economic, and social value, rather than what she felt mattered more: useful passions.

For Beauvoir, choosing a useful passion is one path to true freedom because it allows us to activate our individual value systems for the greater good. It’s the modern equivalent to “do what you love, the money will follow,” or maybe even just proudly passing on a midmorning donut because you’re passionate about diabetes prevention.

Rate your complacency

In “The Ethics of Ambiguity,” her famous essay responding to Existentialist philosophy, Beauvoir shares this idea of useful passions and goes on to categorize different spectrums of passion to showcase the differences between a complacent society and an active, healthy one.

Here is a quick A.I.-generated summary of Beauvoir’s Ways of Being:

The Sub-Man – Someone who avoids freedom and responsibility by sinking into inertia and passivity.

The Serious Man – Someone who submits his freedom to external values or causes, treating them as absolute (e.g., ideology, religion, nation).

The Nihilist – Someone who rejects all values after discovering their contingency but refuses to create new ones.

The Adventurer – Someone who embraces action and freedom for its own sake, without regard for others’ freedom.

The Passionate Man – Someone who gives his freedom to a chosen object of passion, losing himself in it.

The Genuine (or Free) Man/Woman – The one who recognizes both their own freedom and the freedom of others, acting authentically and ethically.

Beauvoir’s ‘Ways of Being’ and their modern marketing equivalents

While Beauvoir meant at the time that happy people don’t want to kill people, don’t have a need to steal or beg, useful passions remain a prescient assessment of who we are as writers and communicators today.

As communicators, passion, freedom, choice, joy? These are the calling cries of our people, and if you haven’t already identified where your own audiences land on Beauvoir’s “Ways of Being” list, this might help:

The Sub-Man = The Security Seeker who wants reliability, tradition, and lifetime access to AARP.

The Serious Man = The Loyalist who lives for rules but wants others to make them. They may be a little fascist. I don’t know.

The Nihilist = The Resident Skeptic who hates mainstream everything, but loves starting unwinnable arguments and Cards Against Humanity marathons.

The Adventurer = The Risk Taker and Red Bull addict who shows up wearing a cervical collar and a black eye after a long weekend. Because risk? It’s worth it.

The Passionate Person = The Martyr is the kind of audience nonprofits like to go after: they’re deeply invested in community building and love to give of themselves.

The Genuine (Free) Person = The Unicorn, or someone who balances freedom with responsibility by ethical, sustainable means that do as little harm as possible.

Right now, existential freedom in the age of algorithms rewards clickability over conscience. Understanding how economic, political, religious, and other belief systems control how we perceive our lives certainly extends into how we communicate.

De Beauvoir’s ‘useful passions’ bring deep meaning—and great responsibility—to the work of modern communications.

As Beauvoir might say, don’t be doing your work as a communicator or creator simply for the money or accolades or other ego-driven impulse. Be in it because you are (or once were) passionate about it.

For me, that’s returning to her work more than two decades after I picked up “The Second Sex” in a Women’s Studies course and realizing we’ve only come full circle once again: the human experience will always be steeped in freedom, joy, choice, and love. It’s up to us as communicators to showcase the power of those emotions.

Whether your audiences are in Sub-Man territory or Passionate People, how you communicate with them has the potential to change their minds, incite choice, and alter their perceptions of their own value in society.

For me, that looks like returning to the foundations of why I became a writer, why I remain passionate about communications, and how I can help others be better communicators. Writing is my useful passion. Communicating well is the sum of the total value of that passion.

Which brings me to my most favorite lesson: Be a communicator because it brings you joy, it makes you feel useful to others, and contributes to the dismantling of misinformation, distrust, and attention deprivation. Our futures depend on this level of literacy, and the world will be looking to us communicators for guidance in the months and years to come as we navigate new, troubling disruptions to our collective intelligence as a sentient species.

May we communicators, writers, and creators show up with useful purpose.

Thanks, Simone, for the wisdom. For the words.

Sources:

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Ethics of Ambiguity. Translated by Bernard Frechtman, Open Road Integrated Media, 2018.

Every writer needs an editor.

Here me out.

Editors are coaches disguised as track changes and suggested edits.

And contrary to what many believe, we aren’t out to prove you’re a crummy writer.

I say it all the time: editors love your writing more than you do, but that’s kind of just the beginning.

Editors can help you a lot

They help you address inconsistencies. From repetition to header hierarchy to contradictions, editors are key messaging masters who want to make sure yours are being used as intended.

Restructuring is our jam. Several of my writing mentors throughout the decades have possessed the same mantra: “Best words, best order.” Restructuring writing is a craft all its own.

Checking for accuracy makes us get up and dance. Editors love factchecking, and we’re an expert solution for anyone interested in eradicating the spread of misinformation.

No matter how many “final, final” drafts we send back and forth, we got you. Editors who love what they do see your work with an objective eye but with the heart of a writer. We want your work to make sense — and make feelings.

How editors become coaches

Over time, working with an editor (especially the same one for a number of months or years) yields an unwavering trust.

That trust leads to open, honest discussions about not only your writing, but your entire communications process. Maybe even your purpose as someone who has something to say. With an editor:

- You learn to be a better writer, which makes you a better communicator.

- You have more headspace to focus on the process, not the end result.

- You begin to see your writing strengths and weaknesses.

- You learn how to work in drafts to produce cleaner efforts from the start.

- You have validation and support as you build on your best ideas, strategies, and stories.

When you work with an editor, the results can be positively astonishing.

- Your writing process gets more efficient over time.

- You spend less time drafting and more time planning, organizing, and polishing.

- You have more headspace for rest and someone to celebrate your wins with you.

What to look for in an editor.

Hire an actual editor and look for one who:

- Sees your writing’s strengths first, weaknesses and errors second.

- Encourages you to enjoy the process of creating stories.

- Wants your writing to be the best and most authentic as can be.

How to find an editor.

I’m not sure when exactly we lost the role of editors, but my vote is to bring them back into the forefront of our communications teams where they belong, leading not only the accuracy of our work, but the ethical and purpose-driven visions behind that work.

If you’re curious about what working with an editor looks like, reach out and ask one on LinkedIn.

Or ask me! You can do that by emailing me at lonna@gardencommunications.com where I can be found at all hours of the week.